Trigger warning: Gun violence, racism and death.

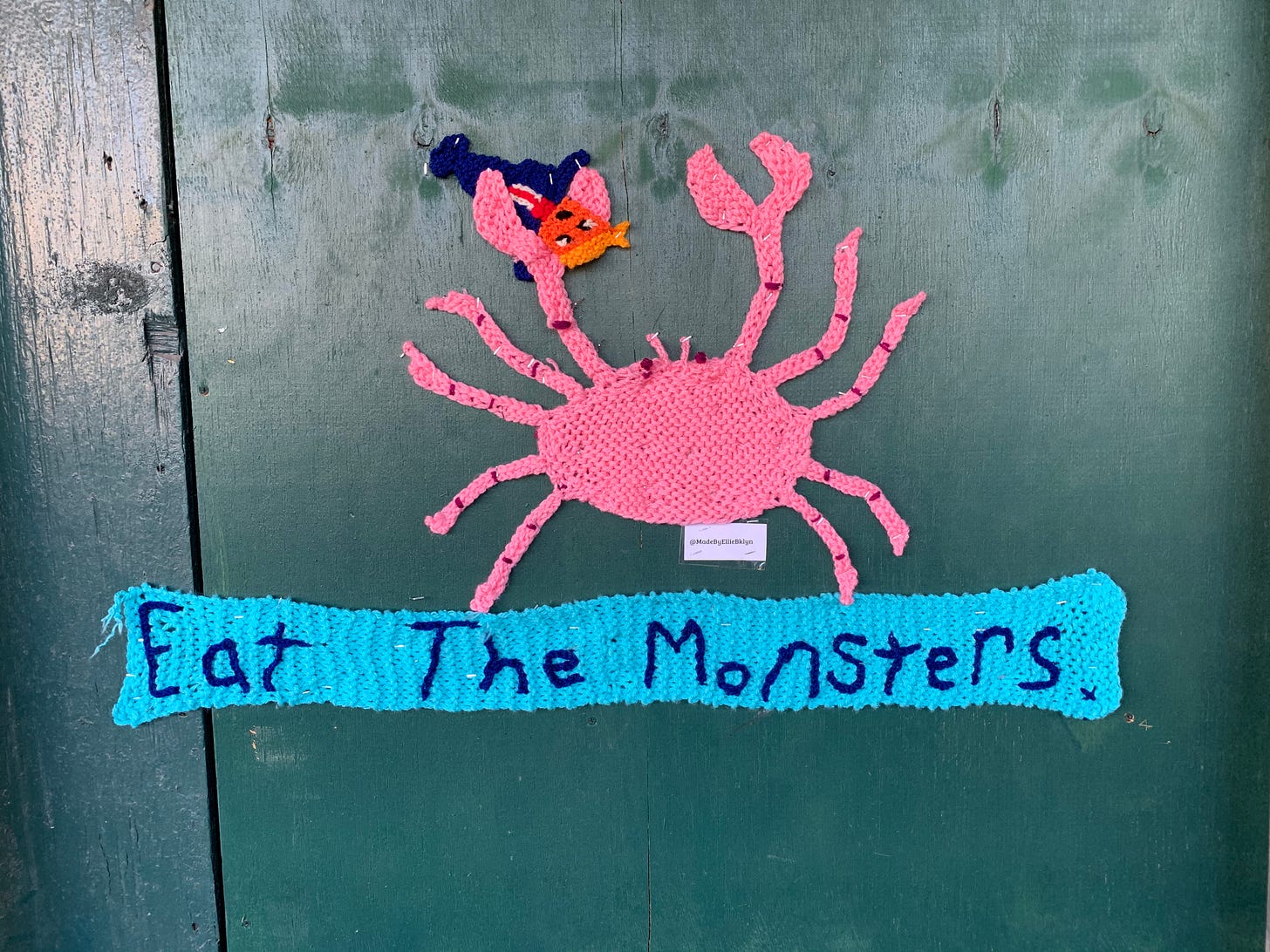

Art: Ellie d'Eustachio

Yesterday I awoke to the news of the police shooting of Jacob Blake in Kenosha, Wisconsin. Shot multiple times in the back in front of his three children inside his car. He’s now fighting for his life.

The night before, Trayford Pellerin was shot and killed by police as he walked away from them in Lafeyette, Louisiana. Yesterday was also the one-year anniversary of Elijah McClain’s lethal ketamine overdose at the hands of Aurora, Colorado police as he was walking home. It’s been over five months since Breonna Taylor was shot dead by police in her own bed—no one has been charged.

We know what the news will be tomorrow. What it has been for decades.

This week I’ve been thinking about guns in America even more than usual because I was home during a shooting on my corner.

Last Wednesday, my friend Stephen was over for a visit. We were sitting on the couch of my sixth-floor apartment when gunshots rang out, very near. I ducked, getting my head below the bulk of my couch, as if a few pillows would save my life from a stray bullet. Multiple shots went off within seconds, but time stretched enough for Stephen to attempt to look out the window to see what was going on. “Stephen, get down,” I said to him, pulling his arm.

When the sounds stopped and we looked out the window, two bodies lay sprawled in the street. On the left, a white man lying facedown was being tended to by a violet-haired woman who I now know is his wife. On the right, a Black man lay on his back, bleeding from his chest. He had no shoes on; later, I spotted them near the corner of the street, near his fallen iPhone. They must have fallen off as he tried to flee.

People immediately started gathering around the bodies, screaming out “Someone call the cops!” I dialed 911 and told the operator there had been a shooting on Ocean and Woodruff. “Ocean Avenue?” she asked. “Yes, I heard seven or eight shots. There’s two people shot,” I said. “Oh, okay, that’s very important,” she said, chastising me for burying the lede. I’ve never called 911 before.

The neighborhood jumped into action, some directing car traffic, some rushing over in their scrubs to see what medical help they could provide. My roommate came out of her room and discovered what had happened; the three of us watched helplessly. A woman dressed in all-white bent down next to the Black man (who I now know is named Malcolm Amede), comforting him. I was so glad she had the bravery and humanity to be with a stranger in his time of need; I was aching thinking of him dying, in pain, alone.

The ambulances arrived after what felt like a long time, but perhaps it was between five and ten minutes. The paramedics cut open the fallen men’s clothes, worked on them, loaded them onto stretchers, took them away. A woman arrived on the scene and saw Amede; she started screaming primal sounds of grief, shouting “That’s my baby brother!” I covered my mouth and began to cry. More people who knew him showed up. They tried to be near his body, to get into the back of the ambulance; the police told them no, restrained them. A man tried over and over again to yell Amede’s name through a small, closed window in the back of the ambulance, using his hands to try and pry it open. I could hear a woman agonizing about how many deaths there had been in the neighborhood, saying she can’t take this shit anymore.

We watched as dozens of police trickled onto the scene, caution tape rolled out, evidence marked by yellow numbers. A single policeman stood watch over a puddle of vibrant red blood for hours. It was still an active crime scene when I went to bed around midnight, putting on an eye mask so I wouldn’t have to see the red, white and blue sirens flashing on my bedroom ceiling.

That day, I had talked to a Daily News reporter about what I witnessed. Police sources said “a gunman sat in a parked gray BMW, waiting for his mark to walk by on Woodruff, and opened fire” on Amede. There’s been a spree of gang violence in the neighborhood lately. Yesterday, I learned new facts about the victims. Malcolm Amede was 18 years old, a brand new father who was on his way to a memorial for another man who was shot dead while on his way to another gun violence victim’s memorial. Neighbors told me he had tried to return fire on the car with his own gun; he died with it nearby. The white bystander who was shot, 33-year-old Sam Metcalfe, lived, but is unlikely to ever walk again. A GoFundMe page set up to support his recovery states that his wife stepped out to get toothpaste, and he went with her to hold an umbrella for her in the rain.

I am mourning for both of them. They are both my neighbors.

Gun violence is up 72% in New York City year over year; much of the nation is experiencing a similar spike. People are jobless and hungry and desperate. 2020 takes and takes and takes.

My roommate, Melissa McMillan—a Black singer-songwriter who Minerva loves dearly—has lived in this building years longer than I have. (I asked her permission to write about our discussions here.) She has always felt safe here, as have I. But after experiencing this shooting and learning how many have been happening within a few-block radius of our apartment, she’s felt more scared to go outside.

She also felt confused about the dichotomy of desires she experienced for herself and her neighborhood after this happened. She’s been involved in Black Lives Matter protests and local politics all summer long. This shooting was one of the violent, life-threatening situations we need the police (or some form of trained tactical unit) to respond to. The police have ramped up their presence over the last week in my neighborhood because of the many shootings happening here; there are signs posted offering $1000 rewards to people with information about illegal guns. Melissa wants to feel safe here and wants police presence for crime prevention, to dissuade people from shooting onto busy street corners in the middle of the day. But she also knows that for our majority-Black neighbors, police presence so often equals oppression.

It is hard to comprehend how very far away my country is from a law enforcement system that is truly community-focused, that actually serves and protects all people—not just white people. I’m learning more about police abolition and what it would look like to defund and dismantle the police, as Minneapolis has pledged to do. It might look like a tactical force only to be called in life-threatening situations, and well-funded social services to help ease issues of homelessness, mental health and neighborhood disputes. Right now we ask our police to solve every issue, from violent crime to a rabid animal to a person acting a bit oddly in public. They are not trained and equipped to do so.

Melissa and I talked about the vast intersection of gun violence, systemic racism, poverty, domestic violence, and so many other issues. She noted how so much access to guns makes for higher suicide rates and more domestic violence murders of women and children, and how gang violence is precipitated on the existence of deep social problems such as wealth inequality and education systems that fail Black kids.

There is so much fixing to do, and it’s all so interconnected. It feels so overwhelming. Neither Melissa nor I have the answers. There are no easy answers. But change has to come. And white people have to demand it.

A few times a year, I return to Mother Jones’ reporting on mass shootings in the USA, with data dating from 1982. Mass shootings (defined here by four or more people killed, excluding domestic violence or gang or criminal activity) have tripled in frequency since 2011, with a mass shooting occurring every 64 days on average. And the killers are mostly white men. As the author of that article states: “It’s not a matter of if, but when and where the next mass shooting will happen: It might take place at another shopping mall, or college campus, or suburban office building, and probably not long from now.”

According to the nonpartisan organization Gun Violence Archive—which defines a mass shooting as any gun violence incident where four or more are killed besides the shooter—there have been 395 mass shootings in 2020. Today is the 237th day of the year.

The National Rifle Association (NRA), which is designated a charitable organization, donated $30 million to Trump’s presidential campaign in 2016. (New York’s Attorney General recently filed a lawsuit to dissolve the NRA due to an alleged illegal use of funds by organization leadership to do things like go on vacations and give lucrative contracts to family members.) Republican members of Congress are overwhelmingly the beneficiaries of the gun lobby’s donations, which total millions. Most Americans—93% of Democrats and 82% of Republicans—agree that common-sense background check gun laws should be passed, according to a recent Pew Research Center poll. But Congressional Republicans, particularly Mitch McConnell, have kept Congress from passing these simple laws that could save so many lives.

My friend Lia Albini is the deputy communications director for Connecticut Senator Chris Murphy. She has worked for him for almost six years in Washington, DC and is my go-to person for political questions. In 2012, one month after Murphy was elected to the Senate, 20 children and six educators were gunned down at Sandy Hook Elementary School. Murphy has been a major voice in the gun violence prevention movement ever since.

“One thing we talk about a lot in my office is that Sandy Hook was really the birth of the modern gun violence prevention (GVP) movement,” Lia says. “It was mind-boggling to a lot of people that Congress wouldn't pass something as common-sense as background checks after Sandy Hook. But part of the reason we failed to pass background checks in 2013 is because the NRA was an organized political machine, and we were not.”

Lia has seen GVP grow into a powerful political movement over the last eight years, building a broad coalition of supporters and driving people to vote on this issue. But Mitch McConnell has kept GVP bills from the Senate floor. “I really believe that we will pass background checks (and hopefully other laws),” Lia says, “and when we do it will be because of the organizing and power-building work that volunteers, gun violence survivors and GVP leaders have done over the last eight years.” The change in hearts and minds she’s seen, as well as the success GVP groups have had in passing legislation on the state level, brings her hope.

I can’t say I feel much hope when it comes to curbing gun violence in my country. But I know with certainty that I will vote for the leaders and laws that are not complicit in the senseless, preventable deaths of more innocent Americans. I won’t look the other way.

I’ve thought a lot about how I could die anywhere, anytime from a shooting—in a mall, school, movie theater, farmers market, sitting on my couch at home, asleep in bed. After Sandy Hook, my country decided that we would rather fight for the right to carry firearms than the right for our children to stay alive in their schools. The gun laws haven’t changed since then, and neither has the gun violence or the police violence. It’s clear who gun rights are for in this country: white people. That’s who the NRA shows up for. That’s why white Mark and Patricia McCloskey can stand in their yard and wave guns at protestors, and remain perfectly alive. But Black 12-year-old Tamir Rice is seen playing with a toy gun and shot dead on sight.

I hate that shootings are an everyday occurrence in my country. I hate that I am desensitized to the news. I hate that I’ve seen TikToks by high schoolers joking about how at least they won’t die in a mass shooting now that they’re learning by Zoom. I hate that I saw someone die from my living room window. I hate the heavy burden of grief faced by Black Americans that I will never fully understand.

The shooting on my corner (which is also home to a playground) happened at 3:30pm. I’ve lived in this neighborhood for four years, sharing crosswalks and grocery stores and laundromats with my community. I cross the street where my neighbors were shot every single day. It could have been me. Someday, it might be. Would you be shocked?

Resources:

NPR’s Code Switch podcast: A decade of watching Black people die

Videos of police killings are numbing us to the spectacle of Black death by Jamil Smith

Questions to ask yourself before sharing images of police brutality by Sara Morrison

Call Your Girlfriend podcast: Police abolition

Don’t stop fighting for justice for Breonna Taylor

Showing Up for Racial Justice (SURJ)

Mother Jones’ guide to mass shootings in America

Lia Albini’s suggestions of gun violence prevention groups to get involved with:

Everytown

Moms Demand Action

Giffords

March for Our Lives

Follow me on:

You are not alone!

Hi, I noticed that you're using a photo of my art with your article. I love that you like my art but please credit me if you want to use the image: Ellie d'Eustachio or my instagram @madebyelliebklyn Thank you!!