In my most recent piece for Tribeza, I spoke with Texas artist and current Fulbright scholar Candace Hicks, whose embroidery work I have been fascinated with for years. (For those in Austin, her current show is on at the Ivester through Feb. 22 — go see it!) I wrote about the wonder Hicks’ art inspired in me:

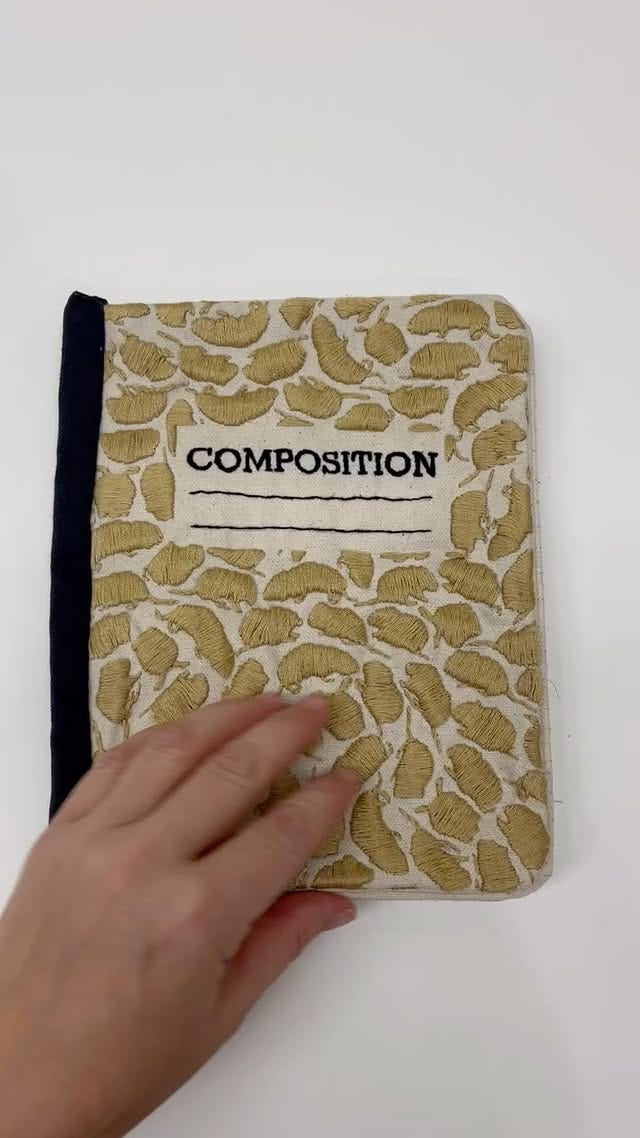

When I first laid eyes on Hicks’ work at the Ivester Contemporary in 2022, I was drawn to it like a child to a shiny balloon. Her series of embroidered notebooks titled Common Threads are meant to be picked up and read, providing an irresistible tactility to a writer and reader like me. Each work resembles the standard composition notebook many of us remember from elementary school days, with several “pages” detailing a moment of profound coincidence in Hicks’ life — every margin and line and word painstakingly embroidered — connecting words and themes gathered from literature, conversations, and experiences. They feel like an intersection between a secret journal and a sci-fi novel.

On coincidence, Hicks says:

“Coincidence makes you feel really weird in a good, undefined way, like very few things in life. The pleasure that you get from them is not really tied to any of your senses. It’s just like a buzzing in your brain or a kind of stimulation.”

I don’t remember exactly what I read on the pages of Hicks’ notebook that I picked up and fondled that first day at the Ivester, but I know it was a story about Hicks reading a mystery. While I went about my life this month, I thought of Hicks’ art, the many mysteries of everyday life, and the art of coincidence.

I spent the first weekend of February feeling extremely brokenhearted for my country, and for my brother. I cried a lot. Then my mother came to visit me for five days, during an 80-degree winter week, and the fog lifted. We saw the traveling Broadway show of Les Misérables (probably my 8th time seeing it in at least four cities and two countries) and she told me, again, the story of how she first saw Les Mis in Los Angeles when I was six weeks old, and cried her eyes out when Fantine sings to her daughter, Cosette, before she dies. This time, we cried together, holding hands in the dark, watching Jean Valjean sing “Bring Him Home,” both of us silently thinking of my brother Chris, who did not come home.

In our downtime, we watched hours of Unsolved Mysteries, the old, original series that kicked off in 1988, the year I was born. (If you haven’t seen the new series on Netflix, it’s well worth a watch.) But many of these mysteries were no longer unsolved — these episodes contained updates of conclusions that happened after the show aired, resolutions sometimes sought for decades and now solved within days: reconnected family members, bodies finally found and peacefully buried by loving family members, rapists discovered living under new names and arrested, the advance of DNA evidence finally closing the case. I came to expect a text update displayed over urgent synth beats at the end of each case, so much so that, when I didn’t get a “solved” update, my heart sank.

My mom went home over a week ago, but I haven’t stopped watching Unsolved Mysteries from the ‘90s. The separation of time makes the cases feel a bit removed, less wrenching than the chaos happening in this timeframe, and I am oddly comforted by the answers I find there. I get a much-needed hit of dopamine when I see yet another mystery solved.

It’s nice to have the answer to a question now and then. The things I don’t know are immeasurable, untouchable. The future, always unknowable, feels terrifyingly so right now. We know even fewer answers than usual about what the future will look like for our country, our communities, our safety. Personally, I’m not even sure where I might be living in a year.

I want to know some answers.

I last solved a mystery on December 22, 2023.

My grandfather, Chuck, was temporarily living in a rehab hospital in Las Vegas, dealing with all kinds of end-of-life issues (after recovering from an appendectomy at 90 years old, and a spin out and crash on the freeway while being transported in a medical van): low blood count, swallowing issues, slurred speech, painful IV infiltration.

He was doing a bit better under the watchful care of my mother, but just as I arrived to visit for the holidays, both she and my dad came down with Covid, hard, and were relegated to bed.

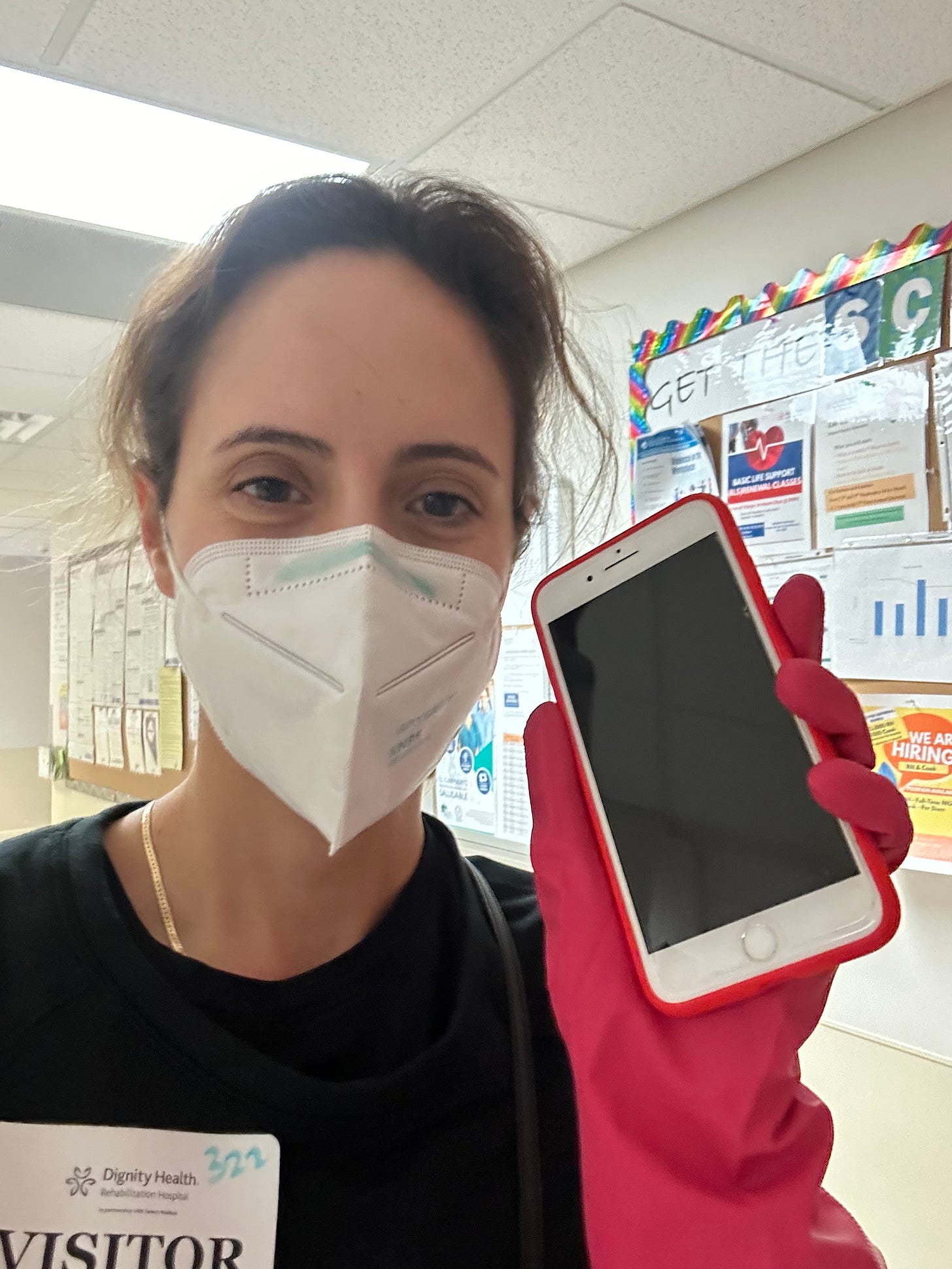

I continued to visit my grandfather for a couple of days, until I felt it was no longer safe to do so because I’d likely come down with Covid too. On Friday, when I went to visit him, he couldn’t find his iPhone. This was strange because he always kept it with him in bed, even right on top of his body, and he couldn’t walk anywhere without assistance, so the phone had to be close by. Did it get thrown in the trash with his bedsheets? Was it taken away on his lunch tray?

That cell phone was our only way to keep in contact with him while we stayed at home sick and quarantining, and he had nothing else to do other than sit in bed and watch TV. I searched high and low, but eventually gave up, said my goodbyes, and drove home.

I called my sister, and she gave me a great idea — use FindMy to check the phone’s location. When I got home, I carefully asked my mom to give me my grandpa’s iCloud password without alerting her that the phone was missing; she was sick as a dog and I didn’t want to add to her stress.

I logged on and saw the phone’s dot — it was right by the rehab hospital. I went to sleep with a mission: I was going to find that phone.

The next morning, I started my wild goose chase bright and early. I felt determined, but also strangely lucky. “I am going to find this phone,” I said out loud to myself over and over on the drive over. And I believed that I would.

Once I arrived, I followed the dot to the trash bins behind the building. I played the FindMy chime over and over, but heard nothing. Back there, I found a truck loading up dirty laundry to take it away, a man putting bin after bin into the truck. I told him what I was up to, and if I could come up and listen for the chime, but he told me to go inside and talk to the staff.

I did, told them my story, and they helpfully took me to the kitchen and rooms filled with soiled linens so I could ring the chime and listen. Nothing. Finally, the helpful nurse took me back out to the laundry truck, where the guy was almost finished loading up. He still wouldn’t let me on the truck bed, so I asked him to please listen for the chime.

We all huddled in silence, straining our ears — until he said he heard something. I played the chime again, he listened harder: “I think it’s in here,” he said, pulling a bin filled with bags of laundry off the truck. I pressed my ear close to the piles of bags and listened.

“Ding ding DING ding ding da ding.”

“It’s in here!” I exclaimed.

Donning gloves, I pulled out the bag in question and tore it open, the musical pings guiding my impatient hands through sheets and pillowcases. Until finally, there it was, my grandfather’s iPhone with a red case. I held it up in my right hand triumphantly. The nurse and the laundry truck guy cheered for me, and I thanked them effusively for their help.

I had rescued my grandfather’s phone minutes before it would have been lost to the laundry truck gods forever.

I giddily went upstairs to my grandfather’s room to share the good news. “Grandpa, guess what? I found your phone!” I told him, pulling it (freshly cleaned) from behind my back. I told him the whole story, and his huge smile made every moment worth it. Then, he immediately checked his stock prices. Same old grandpa.

Putting on my Olivia Benson hat and actually solving this mystery was a rare high, one I lived on for awhile. And doing this service for my grandfather meant everything to me.

I never did get Covid on that trip, despite nursing my parents through a decisively shitty Christmas. At that point, we still thought my grandfather would recover. We didn’t yet know the answer: that he would die just three months later.

A couple of Saturdays ago, I took myself on a long walk on an 85-degree February day. I got to the bridge at sunset and took off my headphones to listen to the guitarist sing Spanish songs. He played “Bésame Mucho,” and I smiled at my parents’ love song of 50 years. After, I went up to Venmo the artist and noticed his name: Javier Jara.

“Javier?” I introduced myself. “I’m Jillian Anthony — I interviewed you for a story for CultureMap last year.” We briefly chatted about music, life, Austin, and I walked away smiling, overjoyed at this coincidence — something that “makes you feel really weird in a good, undefined way, like very few things in life.”

I left my headphones off as I walked an hour home in the twilight, until I came upon a DJ booth set up in the middle of Zilker Park. I followed my curiosity and sat down, watched 20-somethings with High noons dance and bob their heads to club mixes, dogs running everywhere, the glowing downtown skyline looming over Lady Bird Lake.

I don’t know what will happen in the future. But, sometimes, the present feels a little perfect.